|

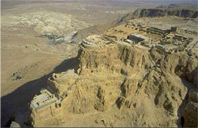

DELTA DREIDEL & SEVIVON COLLECTIONSDelta has reached into history and developed a brand new exceptional pen collection which has great meaning, the Dreidel collection ballpoint, rollerball and fountain pens.The Dreidel pens feature a small dreidel which fits neatly into the pen cap. The dreidel (Yiddish) or sevivon (Hebrew), are four-sided spinning tops that children play with, on Hanukkah. Being made in a numbered edition, the Dreidel (which means spinner in Yiddish) pens are made 100% in Italy of the finest Italian resin with solid 925 sterling silver trims. Ballpoint, rollerball and fountain pen are available in four glorious colors (Black, Rose, White and Blue); the fountain pen has a 14 kt gold nib and uses a cartridge or converter. The Sevivon (meaning spinner in Hebrew), is a Limited Edition (358 pieces), Celebration (48 pieces), constructed of Celluloid with vermeil trim with a sapphire on the top of the cap, the fountain pen is lateral lever fill and 18kt gold nib. Sevivon Sov Sov Sov ----- Dreidel Spin Spin Spin The letters on the four sides of the dreidel in Hebrew are (Nes Gadol Haya Sham, נס גדול היה שם “A great miracle happened there”) referring to the miracle of the oil that took place in the Beit Hamikdash in the Holy Land. In Israel, the fourth side of most dreidels is inscribed with the letter (P), rendering the acronym (Nes Gadol Haya Po, נס גדול היה פה “A great miracle happened here”) referring to the miracle that occurred in the land of Israel. Some say the dreidel game is played to commemorate a game devised by the Jews to camouflage the studying of the Torah, which was outlawed by the Greeks. They would gather in caves to study and when alerted to Greek soldiers coming, they would hide their scrolls and spin tops, so the Greeks thought they were playing a game, not studying. Hanukkah, celebrated for eight days and nights, starts on the 25th of Kislev on the Hebrew calendar. The word “Hanukkah” means “dedication”. MenorahThis is one of the oldest symbols of the Jewish faith, the seven branched candelabrum used in the Temple. In Israel, the Hanukkah menorah is called the Hanukiyah. Menorahs come in all shapes and sizes. The only requirement is that the flames are separated enough so that they will not look too big and resemble a pagan bonfire. Ancient menorahs were made of clay. They consisted of small, pearl shaped vessels, each with its own wick, which were arranged side by side. Today’s menorah, which stands on a base from which the branches extend and resembles the holy Temple’s menorah and started to appear towards the end of the Middle Ages.   MasadaMasada today is one of the Jewish people's greatest symbols. Israeli soldiers take an oath there: "Masada shall not fall again." Next to Jerusalem, it is the most popular destination of Jewish tourists visiting Israel. As a rabbi, I have even had occasion to conduct five Bar and Bat Mitzvah services there. It is strange that a place known only because 960 Jews committed suicide there in the first century C.E. should become a modern symbol of Jewish survival. What is even stranger is that the Masada episode is not mentioned in the Talmud. Why did the rabbis choose to ignore the courageous stance and tragic fate of the last fighters in the Jewish rebellion against Rome? After Rome destroyed Jerusalem and the Second Temple in 70, the Great Revolt ended-except for the surviving Zealots, who fled Jerusalem to the fortress of Masada, near the Dead Sea. There, they held out for three years. Anyone who has climbed the famous "snake path" to Masada can understand why the surrounding Roman troops had to content themselves with a siege. Masada is situated on top of an enormous, isolated rock: Anyone climbing it to attack the fortress would be an easy target. Yet the Jews, encamped in the fortress, could never feel secure; every morning, they awoke to see the Roman Tenth Legion hard at work, constructing battering rams and other weapons. If the 960 defenders of Masada hoped that the Romans eventually would consider this last Jewish beachhead too insignificant to bother conquering, they were to be disappointed. The Romans were well aware that the Zealots at Masada were the group that had started the Great Revolt; in fact, the Zealots had been in revolt against the Romans since the year 6. More than anything else, the length and bitterness of their uprising probably account for Rome's unwillingness to let Masada and its small group of defiant Jews alone. Once it became apparent that the Tenth Legion's battering rams and catapults would soon succeed in breaching Masada's walls, Elazar ben Yair, the Zealots’ leader, decided that all the Jewish defenders should commit suicide. Because Jewish law strictly forbids suicide, this decision sounds more shocking today than it probably did to his compatriots. There was nothing of Jonestown in the suicide pact carried out at Masada. The alternative facing the fortress’s defenders were hardly more attractive than death. Once the Romans defeated them, the men could expect to be sold off as slaves, the women as slaves and prostitutes. Ironically, the little information we have about the final hours of Masada comes from a man whom the Jews there considered a traitor and happily would have killed: Flavius Josephus. When he wrote the history of the Jewish revolt against Rome, he included an extensive, largely sympathetic section on Masada’s fall. According to Josephus, two women and five children managed to hide themselves during the mass suicide, and it was from one of these women that he heard an account of Elazar ben Yair's final speech. Josephus probably added some rhetorical flourishes of his own, but Elazar’s speech clearly was a masterful oration: "Since we long ago resolved," Elazar began, "never to be servants to the Romans, nor to any other than to God Himself, Who alone is the true and just Lord of mankind, the time is now come that obliges us to make that resolution true in practice.... We were the very first that revolted [against Rome], and we are the last that fight against them; and I cannot but esteem it as a favor that God has granted us, that it is still in our power to die bravely, and in a state of freedom." Even at this late juncture, Elazar could not accept that the main reason the revolt had failed was because Rome's army was vastly superior. Instead, he dwelt on his belief that the Lord had turned against the Jewish people. Finally, he came to an inescapable conclusion: "Let our wives die before they are abused, and our children before they have tasted of slavery, and after we have slain them, let us bestow that glorious benefit upon one another mutually." Elazar ordered that all the Jews' possessions except food be destroyed, for "[the food] will be a testimonial when we are dead that we were not subdued for want of necessities; but that, according to our original resolution, we have preferred death before slavery." After this oration, the men killed their wives and children, and then each other. I suspect there are two reasons the Talmud omits the story of Masada. First, many rabbis still felt a lingering anger toward the extremist Zealots who died at Masada. We know that Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai had to flee Jerusalem secretly to avoid being killed by the sort of people who died there. Furthermore, at a time when the rabbis were desperately attempting to reconstruct a Judaism that could survive without a Temple and without a sovereign state, they hardly were interested in glorifying the mass suicide of Jews who believed that life without sovereignty was not worth living. The story of Masada survives in the writings of Josephus. But not many Jews read Josephus, and for well over fifteen hundred years, it was a more or less forgotten episode in Jewish history. Then, in the 1920s, the Hebrew writer Isaac Lamdan wrote "Masada," a poetic history of the anguished Jewish fight against a world full of enemies. According to Professor David Roskies, Lamdan's poem, "more than any other text, later inspired the uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto.” In recent years, Masada became widely known through the excavations of the late Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin. In addition to finding two mikvaot (ritual baths) and a synagogue used by Masada's defenders, he uncovered twenty-five skeletons of men, women, and children. In 1969, they were buried at Masada with full military honors. The term "Masada complex" is sometimes applied critically to advocates of right-wing policies in the Israeli government. Political scientist Susan Hattis Rolef has defined this "complex" as "the conviction ... that it is preferable to fight to the end rather than to surrender and acquiesce to the loss of independent statehood." Sources and further readings: Yigael Yadin, Masada. The quote about the "Masada complex" is found in Susan Hattis Rolef, ed., Political Dictionary of the State of Israel, p. 214. See also David Roskies, The Literature of Destruction, p. 358.

|